What are these marketplaces, better yet what is a marketplace? – answer: It is & at the same time not what you’re thinking of.

I spent a portion of my week thinking & talking about marketplaces, particularly marketplace startups. This was primarily driven by this article:

https://themargins.substack.com/p/doordash-and-pizza-arbitrage

Summary:

“Doordash reportedly lost an insane $450 million off $900 million in revenue in 2019

Uber Eats is Uber’s “most profitable division”. Uber Eats lost $461 million in Q4 2019 off of revenue of $734 million. Sometimes I need to write this out to remind myself. Uber Eats spent $1.2 billion to make $734 million. In one quarter.” – Ranjan Ray

The unit economics don’t make sense, 11 years on & Uber is still yet to turn a profit, what am I missing?

Now I pretty much spoke out of the right side of my brain & painted all marketplaces with the same brush. This is partly due to the surge in people wanting to ‘create a marketplace’ for others so they can sell their products online, in simple terms a multi-vendor marketplace. The other part is the surge in grocery delivery businesses with people launching apps, others taking orders via Whatsapp as they build trust within their communities. What I failed to see with my quick criticism & laziness in thought was the WHY this is happening. So I went back to learn about tech-enabled marketplaces, the good & the bad.

Over the course of this letter, we will be tackling a few concepts & I hope I am able to explain them well enough:

- Supply-driven marketplace vs Demand-driven marketplace

- Marketplace assign vs Marketplace assist

- 2-side marketplaces

- 3-sided marketplaces

- Components of a marketplace that make it a difficult business:

-Asymmetry

-Asymptotic network effects

-Switching costs.

The first concept we will tackle is Supply-driven marketplace vs Demand-driven marketplace. What we need to understand is that not all marketplaces are built the same.

“At the heart of “Uber for X” company pitches is the most overrated part of marketplaces: the overriding belief that one marketplace strategy cleanly translates across all marketplaces” – Andrew Chen partner @ a16z

The overarching theme of a supply-driven marketplace is access — by breaking down a blockage, be it cost, trust, or reach, the marketplace is able to deliver goods in a manner that makes it 10 times better than what was already there — think Amazon.

In contrast, demand-driven marketplace is an innate platform, what do I mean by that? the Founder of Tenderpoint perfectly explained to me the difference between a platform & a marketplace:

Platforms facilitate the relationship between users & customers by focusing on the best experience for the user but at their core are marketplaces — think Facebook & their ad business. Facebook is a demand-driven marketplace which is an innate platform, as are all other social networks. One of the reasons marketplaces are as popular as consumer socials are —is because of network effects (we’ll talk about network effects later).

The second concept we will tackle is Marketplace assign vs Marketplace assist. This concept is from Ben Gilbert the co-founder of a venture studio called PSL in Seattle, USA. Marketplace assign is when the marketplace matches the user & the customer, think about UBER & other e-hailing companies, when you request a ride you don’t pick who your driver is, the driver gets assigned to you based on proximity — even the customer gets assigned to the driver. Marketplace assist is when you get to choose what you want on the marketplace, think Airbnb, you can choose whatever property you want. The distinction between marketplace assign & marketplace assist is important because of the aggregation of supply & demand. If the marketplace assigns it’s important for the company to focus on supply aggregation & if the marketplace assists, it’s important for the company to focus on demand aggregation. Okay, what does this mean? Again, think UBER — UBER needs to spend most of its time recruiting drivers to make the marketplace work, an influx of drivers make the marketplace more important, UBER would rather have 1 more driver than 1 more rider — even though the rider is the customer. Marketplace assist focuses on demand-aggregation — think Facebook’s Ad business — It is more important for Facebook to profile more users for brands to target than it is for Facebook to recruit brands to advertise, therefore Facebook focuses on the experience of the user first (platform) — even though the brands pay the bills.

If someone comes to you & says ‘Marketplace’ automatically your mind pictures chaos of people moving between stalls, buying goods & services. Keep that picture in your mind it will be useful when we talk about the components of a marketplace that make it a difficult business.

Most people are familiar with 2-sided marketplaces in e-hailing or e-commerce or proptech, where demand is matched with supply, vice versa. People are familiar with the UBERs & the Bolts of the world, the Amazons, the Airbnbs. In South Africa, Takealot is morphing into a marketplace, proptech is another attractive sector with Houseme & the newly launch Flow 2.0. However, the phenomena I want to focus on is the 3-sided marketplace.

It goes back to 2010 when a young Canadian by the name of Apoorva Mehta quits his job at Amazon to start a company, a social media company for lawyers (terrible idea), that ultimately failed but he continued to persevere until his next company in 2012. The premise around that next company was: can groceries be delivered to peoples doorsteps via an app within 1-hour. The idea had been tried before, in fact even 16 years before Apoorva had the idea of Instacart, Louis Borders started a company called Webvan — a grocery delivery company that delivered groceries to customers within a 30-minute window. This sounds all too familiar but the innovation by Instacart is not the idea, its the execution of it & the zeitgeist effect. Apoorva & his team started the business in the mobile & independent contractors age — the zeitgeist. How grocery delivery works now is a customer picks groceries on an app, the app connects to a pool of shoppers, a shopper accepts the order & goes shopping on behalf of the customers, in the background the app connects to another driver app, the driver picks up the goods from the shopper & delivers them to the customer — That’s a 3-sided marketplace. Webvan went on to die during the 2001 dotcom crash but Instacart birthed an entire industry of copycats that we now see today. Connecting 3 different people with different incentives seems like a very difficult thing to do, probably because I have never tried to, but skepticism of the underlining technology is still fair.

At the core though, a marketplace is basically a collection of buyers & sellers with three fundamental components that make it a difficult business model:

Asymmetry: Marketplaces are asymmetrical meaning there is a constant imbalance in supply & demand. Sometimes demand outweighs the ability to supply — think early lockdown when everyone was jumping on Zulzi & OneCart to the point where they crashed & could not handle the demand. Now that is not necessarily a bad problem, Zulzi & OneCart went on to raise capital over the last month so they can invest more in their technology. A bad problem is when supply is low, imagine if you were stranded, opened the UBER app & found that there are no drivers in your location, now that is a terrible problem for UBER & for you. You can argue that Zulzi & OneCart suffered from a supply-side problem but would be a lie. I think the problem was more tech-related & them resorting to Mechanical Turks.

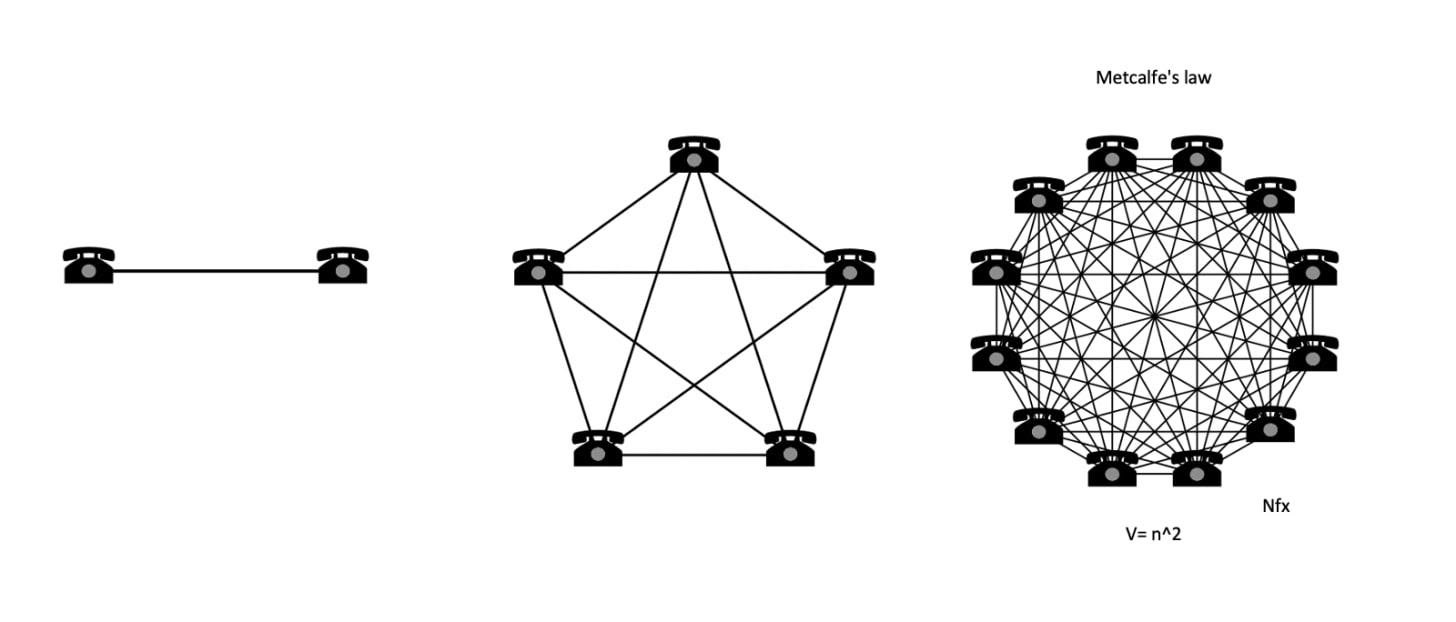

The second component is the Asymptotic Network Effects. Remember the picture of the market you had in mind, if there were only 4 stalls in there, that wouldn’t be a valuable market — now if they added 50 stalls with a variety of things such as drinks, food, clothes, jewellery etc would that be more enticing to you? Yes, of course, you would have an abundance of items to choose from. Now imagine if they added 200 more stalls & you could barely walk through the market, that would be a terrible experience not just for you but the vendors as well. Pile on competitors then it becomes a zero-sum game at scale.

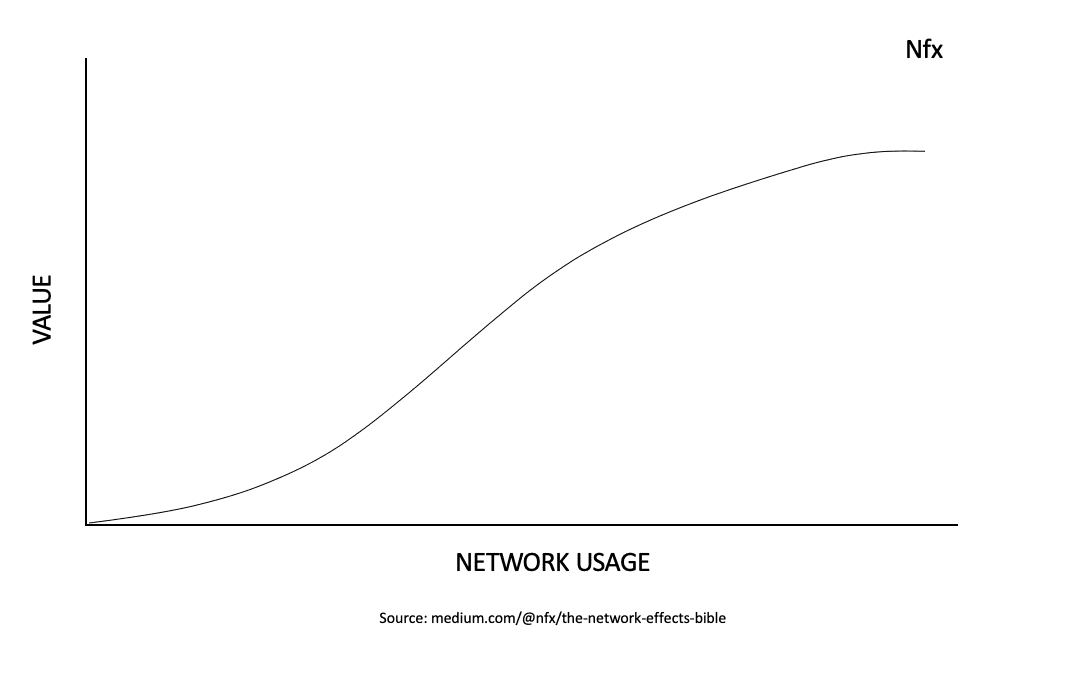

basic definition of network effects: as usage of a product grows, its value to each user also grows. In some cases, however, network effects can start to weaken after certain point in the growth of the network. Growth in an asymptotic network, after a certain size, no longer benefits the existing users. – James Currier Managing Partner @ NFX

But getting there is a good problem, the value of the network is derived from its ability to get additional users. In the early stages of a marketplace, the network is often fragile; if your friend told you not to use a particular service you would probably tell another friend who then tells another friend etc. This can be compounded by non-existent switching costs.

Switching costs are most visible in supply-driven marketplaces such as e-hailing & grocery delivery. The customers, as well as the drivers, are not loyal to any particular app, the cost of switching between apps is almost zero. This means that driver churn is high & customers can easily move between competitors if they experience poor service. The concept of the ‘the devil you know’ does not apply here, consumers are loyal to the experience & not to the app itself.

Switching costs are most visible in supply-driven marketplaces such as e-hailing & grocery delivery. The customers, as well as the drivers, are not loyal to any particular app, the cost of switching between apps is almost zero. This means that driver churn is high & customers can easily move between competitors if they experience poor service. The concept of the ‘the devil you know’ does not apply here, consumers are loyal to the experience & not to the app itself.

So what was wrong about my thinking? I didn’t understand the network effects of marketplaces. What was right about my thinking? supply-driven marketplaces never seem to turn a profit, even at scale, due to components that make them a difficult business at every level.

By Ububele Kopo