The History of Loyalty Programs

Our story starts back in the 1700s. The story goes; a small merchant in Sudbury, New Hampshire wanted to incentivize loyalty amongst his customers. So, in 1793 this merchant began giving his customers copper tokens1. Copper tokens had fallen out of favour in the world & were used mainly during hard times as an alternative medium of exchange. By getting copper tokens, customers could use them for future purchases if they accumulated enough tokens. This proved to be very popular amongst merchants as more copied the method well into the 1800s.

From 1861-1864, copper coins like silver & gold were hoarded during the American civil war creating a liquidity crunch & thus the model broke for merchants. To remedy the situation they started minting their own tokens using brass & tin. But this ended with the enactment of the Coinage Act of 1864, effectively making the minting & usage of non-government issued coins illegal2.

Then came a variety of other incentives programs like pre-purchase incentivize for particular items.

The first of these programs was known as trademarks, not to be confused with trademarks. Trademarks were; collectable paper that could be exchanged for items of equal value. These trademarks were sent to loyal customers via a mailing list. B.T Babbitt’s soap company was the first to do this. The 1860s was the boom of the mail-order business. Across the pond, another entrepreneur by the name of Pryce Pryce-Jones was working on a similar concept to selling his wares’ products, & thus the mail-order catalogue business began.

Mailing customers programmes’ became a big business, B.T Babbitt took his trademarks programme further, allowing customers who collect specific trademarks to partake in a profit share scheme. These trademarks were sent to his most loyal customers. The more they spent on his soaps & cleansers the more unique trademarks they got with the ultimate benefit of being included in the profit share scheme.

The success of these early loyalty programmes created an innovation cycle of new programs; checks were created by The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. which became the biggest retail company in the world in the early 1900s. A competitor, the Grand Union Tea Company, was created in 1872, copied the model, & called it tickets. But the most successful of the programmes created in the 1800s were coupons & stamps.

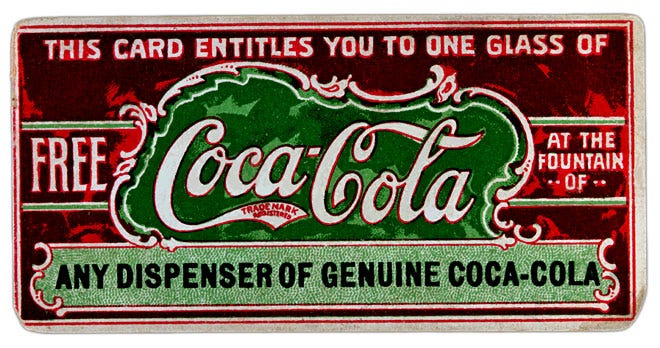

Coupons were created in 1887 by none other than the Coca-Cola company. Asa Chandler had purchased the recipe for Coca-Cola from a chemist in Atlanta. He (Asa Chandler) wanted a new way to market this product, tinkering with ‘Buy one, get one free’ but landed on a ‘Free Glass’ for coupon holders. The strategy proved pivotal for Coca-Cola (plus of course it was a sticky product because of the ‘secret recipe’ *wink, wink*), within 8 years 1 in 9 Americans had gotten at least 1 free glass of Coca-Cola.

Through the early 1900s coupons grew as more companies adopted them. The longest-running coupon, Betty Crocker coupons by General Mills was introduced during the great depression as more Americans wanted value for money. General Mills took the Betty Crocker coupons programme further by introducing loyalty points. By the 1950s coupons & loyalty programmes had become so big that companies could not handle the distribution by themselves, new companies were created to administer loyalty programmes for companies; in came the Nielsen Coupon Clearing House (NCH).

NCH was created in 19573 by Arthur C Nielsen Jr to help retailers manage the reimbursement of coupons. Nielsen is the same company that launched TV advertising measurement4. The job of NCH was to administer & clear coupons, what that means is that NCH was in charge of executing the coupons agreed upon by the buyers & sellers of them. They acted as the intermediary & referee between the buyers & sellers. By 1985, 179.8 billion coupons were distributed in the USA, up from 45.8 billion a decade prior.

Frequent Flyer Points

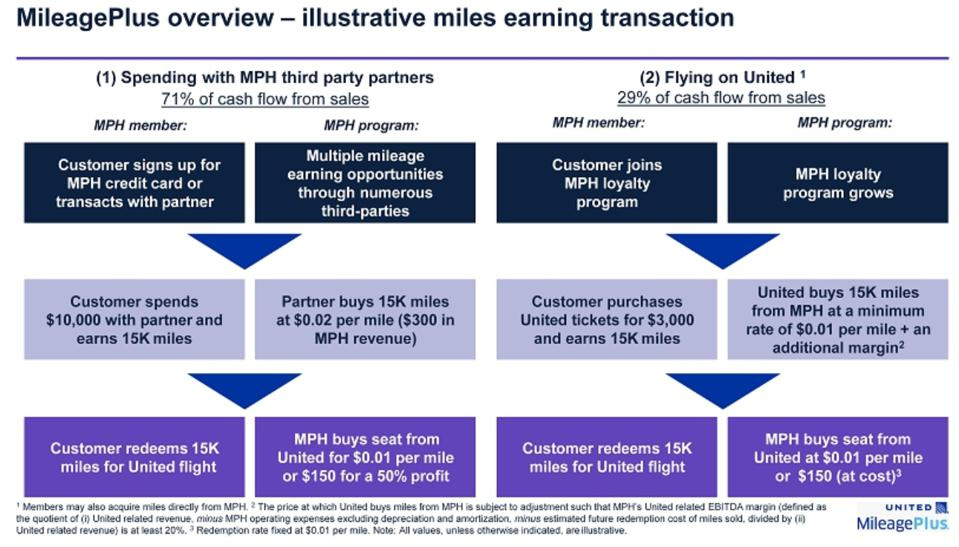

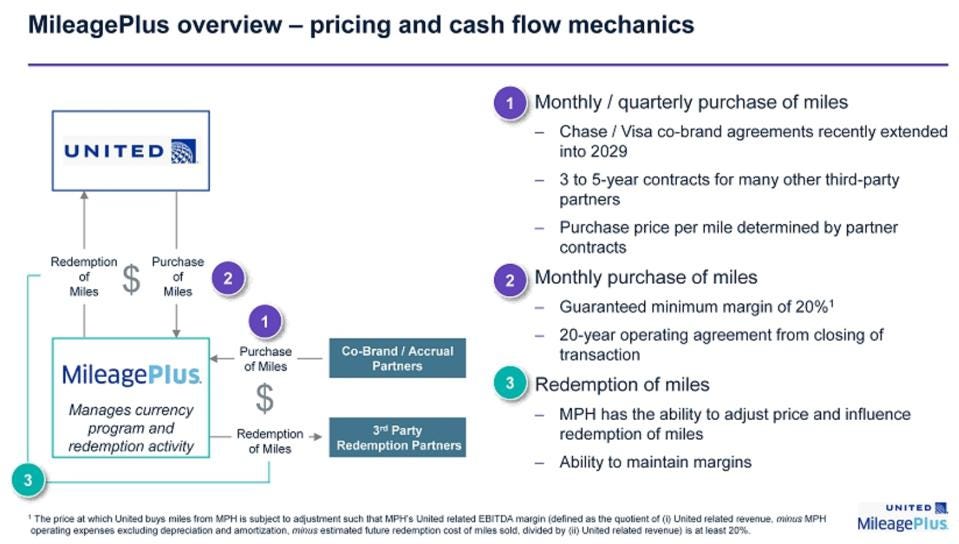

While commercial airlines became prominent in the 1980s, they soon became a commodity. In 1978 the USA deregulated airlines through the Airline Deregulation Act, thanks in part to the complacency of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), & other economic pressures such as the oil crisis of 1973. This law effectively wiped out the guaranteed profits that airline operators had & led to near-perfect competition in the industry. United Airlines had been tracking customers since the 1950s, but the first frequent flyer reward programme was only incorporated in 1972 by the Western District Marketing for United Airlines5. This programme allowed flyers to accumulate points from their travels & redeem them for various incentives, the most common being free flights. But the airline industry became intertwined with card networks & banks. The latter two saw the uptake in these programmes by their highest value customers; High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) & Corporates. This proved a lucrative incentive for card networks & banks alike. For airlines, this became the profit driver. Airlines were now in the business of loyalty but so happened to charter flights in the process.

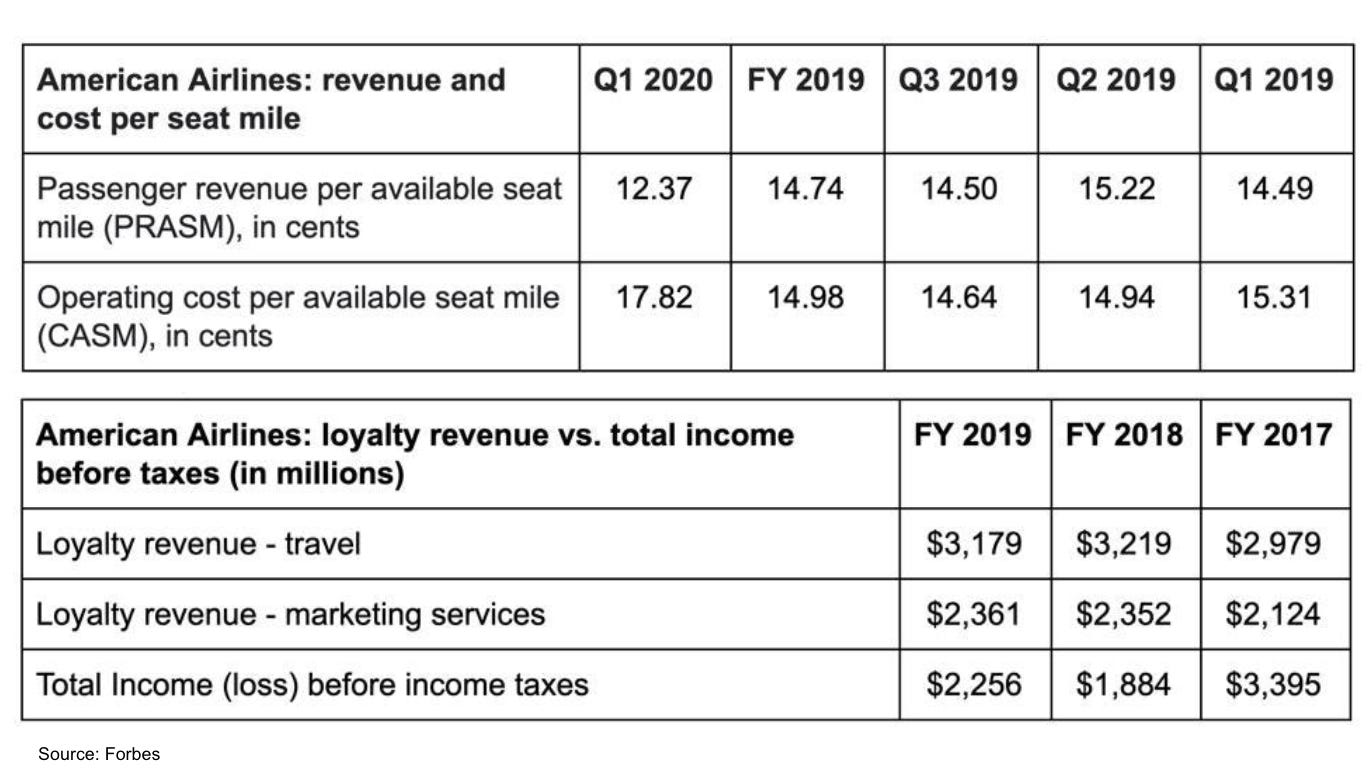

The value of frequent flyer programmes to airlines had been hidden for decades from analysts & the investment community. But recently due to the pandemic, airlines had to appraise their loyalty business in a bid for government loans. According to a Forbes article, American Airlines valued their AirAdvantage programme between $19.5 billion & $31.5 billion. The airline itself has been able to report a profit all due to the margins they generate from their loyalty business.

United Airlines is another one. They run United Airlines’ Mileage Plus. Their loyalty programme is valued at 12x their airline. On an EBITDA basis, United Airlines loyalty business accounts for 26% of EBITDA, albeit on an adjusted basis (American GAAP accounting is pretty weird). Still, according to Forbes, United Airlines received 79% of their cash flow from their loyalty programme compared to 29% from actually core business – flying people & things.

What makes frequent flyer programmes valuable? The answer to this is simple. The reason is that the people who accumulate frequent flyer points do so passively, out of obligation. No matter what they’re travelling for; business or leisure, they do so not out of necessity, but out of obligation. For the thrill of the chase. One can call it chasing a free lunch. It’s almost a game for consumers. For them, it’s unlocking the next level of benefits. For airlines, it’s more lucrative than selling cigarettes on flights.

The Costco Model

Going back to retail… I know the title of this section is called the Costco model when it should actually be the Price Club model but they are 2 sides of the same coin.

The 1970s were an interesting time in the US of A for the business of loyalty. In 1976, Sol Price & his son Robert created what was called Price Club, a wholesale-retail business6. Having had success with his early business, FedMart, Price created the warehouse retailing model. Price initially experimented with club membership for businesses who bought from Price Club. The idea came from FedCo, a cooperative business that also ran a wholesale warehouse for Agri products. FedCo only allowed members of the cooperative (mostly farming families) to buy from the warehouse:

“We ask for a $100 membership equity, refundable at any time upon request. If this would be a hardship, there is a $25 option. Please note that membership is by household (only one membership per household please) or by farm or organization.

Benefits include:

- Our annual members-only newsletter, Digging Deep and Sowing Wide

- A 1% discount on all orders

- An invitation to our annual meeting

- A chance to vote for and serve on our Board of Directors.

- The satisfaction of owning a small part of a successful co-op!”- FedCo website

Price took this model & applied it to retailing, expanding the membership to employees & ultimately to consumers.

…Enter Costco

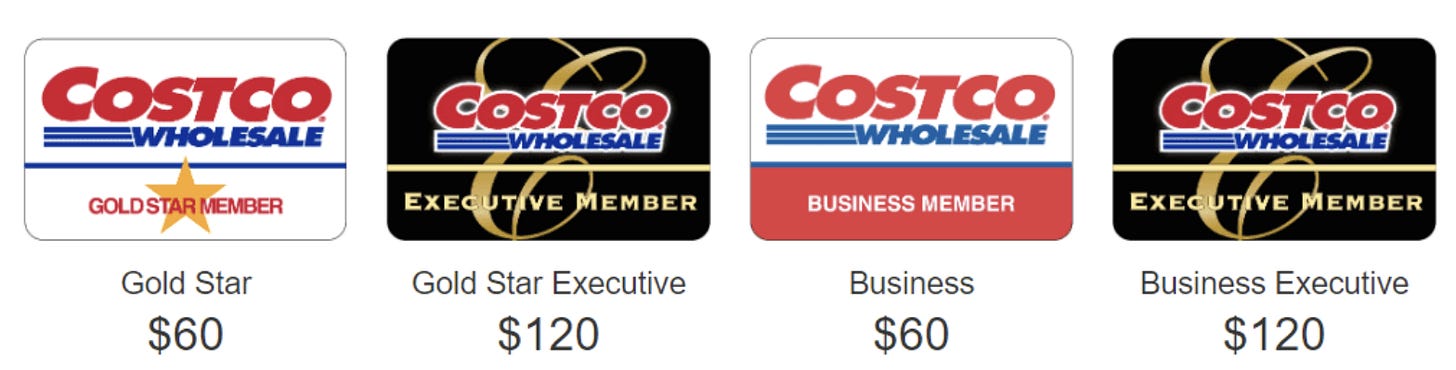

But in 1983 one of his lieutenants left Price Club to create a new business, that business – Costco. Costco like Price Club was (still is) a membership warehouse-retailing club. With lessons taken from Price Club, Jim Sinegal (the lieutenant) & Jeff Brotman built Costco on loyalty.

The business model was simple; keep prices low (i.e no more than 14% markup on high volume items), scale membership base (i.e mechanics of exclusivity create loyalty amongst customers) then leverage that volume to drive the price of goods lower through negotiation with suppliers.

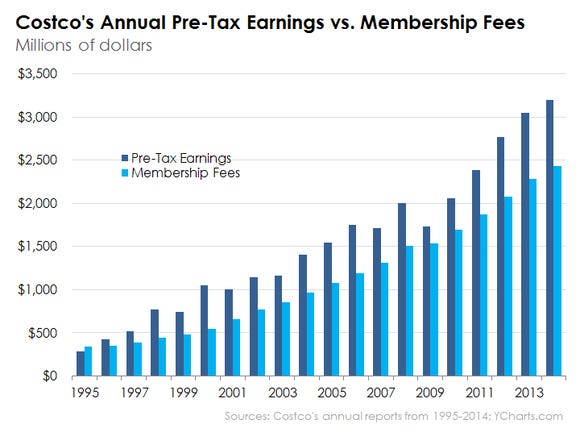

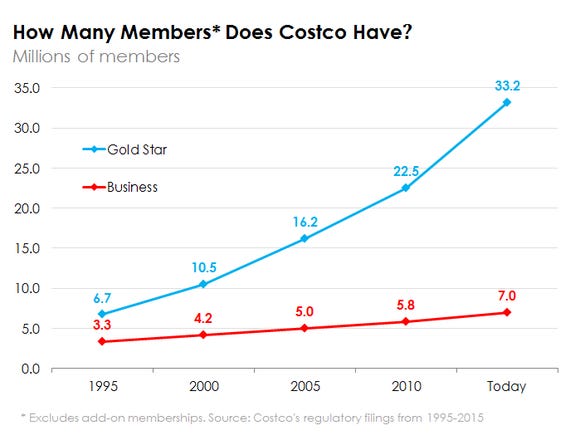

Costco’s membership programme, like Price Club before it, was a success. Within 6 years Costco went from $0 to $3 billion in sales. The growth was driven mainly by the model incentivising bulk purchasing & the margins from membership fees kept them afloat.

By focusing on customer wallets Costco optimized their value proposition: low margins on everyday goods drives high volume in sales. This allowed their customers to self-select. Shopping at Costco is a privilege that many pay a premium for. This has propelled Costco to become a cult brand & one of the biggest retailers on the planet.

Amazon Primed

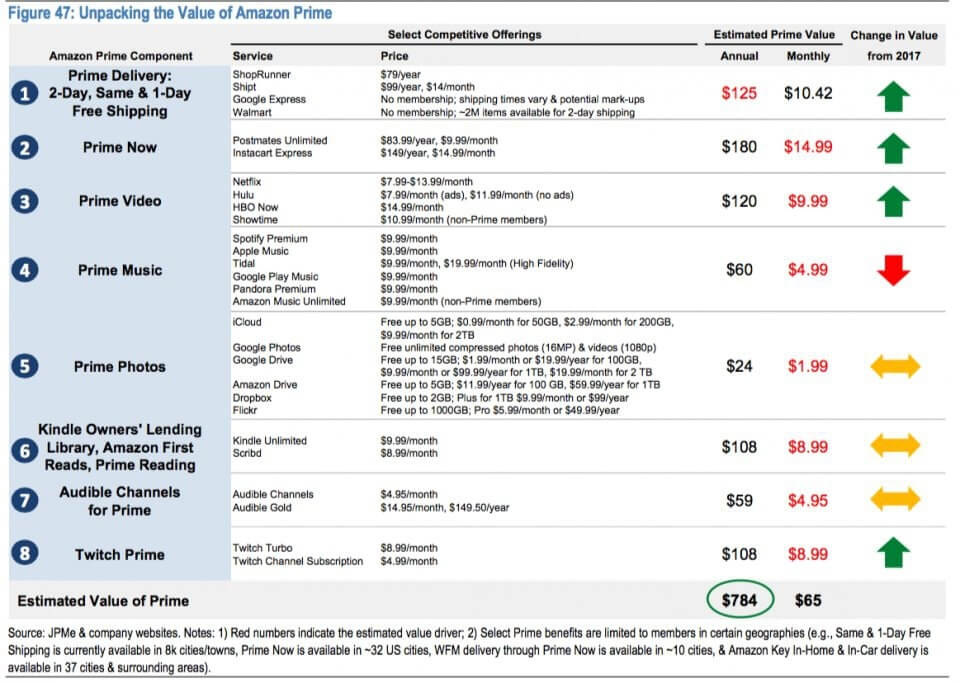

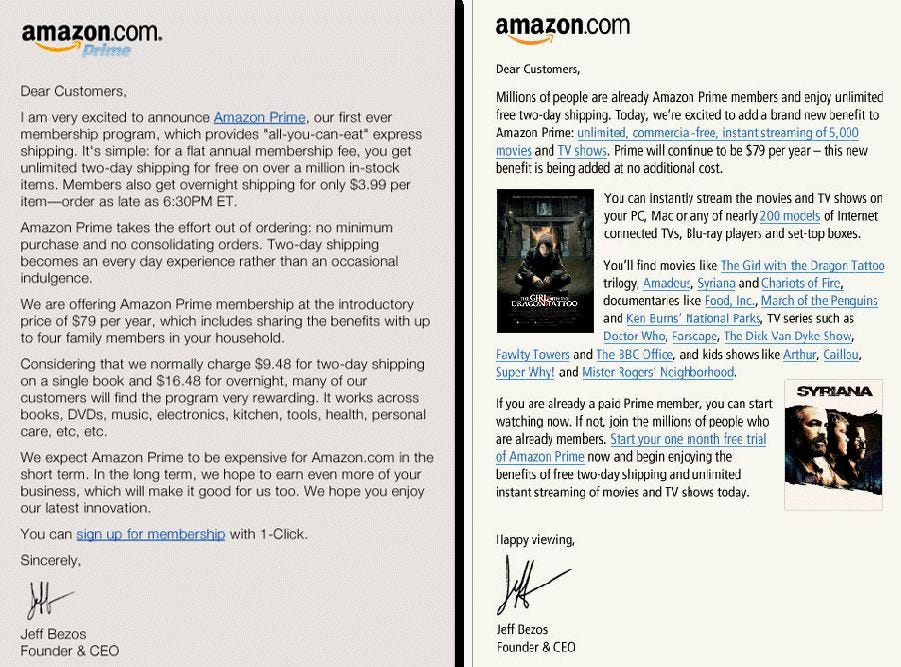

“History does not repeat, but it often rhymes”, a quote from Mark Twain, indicative of what often happens in situations of innovation. People find ways to do the same thing differently. This is what happened when Amazon created the Prime membership. Lessons taken from Costco applied to the internet age. Amazon found a way or a value proposition that customers needed & were willing to pay; to establish a membership programme – Free 2-day shipping. Jeff Bezos said in an email sent to customers on the launch of Amazon Prime:

“We are offering Amazon Prime membership at the introductory price of $79 per year, which includes sharing the benefits with up to four family members in your household.

Considering that we normally charge $9.48 for two-day shipping on a single book and $16.48 for overnight, many of our customers will find the program very rewarding. It works across books, DVDs, music, electronics, kitchen, tools, health, personal care etc, etc.

We expect Amazon Prime to be expensive for Amazon.com in the short term. In the long term, we hope to earn even more of your business, which will make it good for us too. We hope you enjoy our latest innovation.”

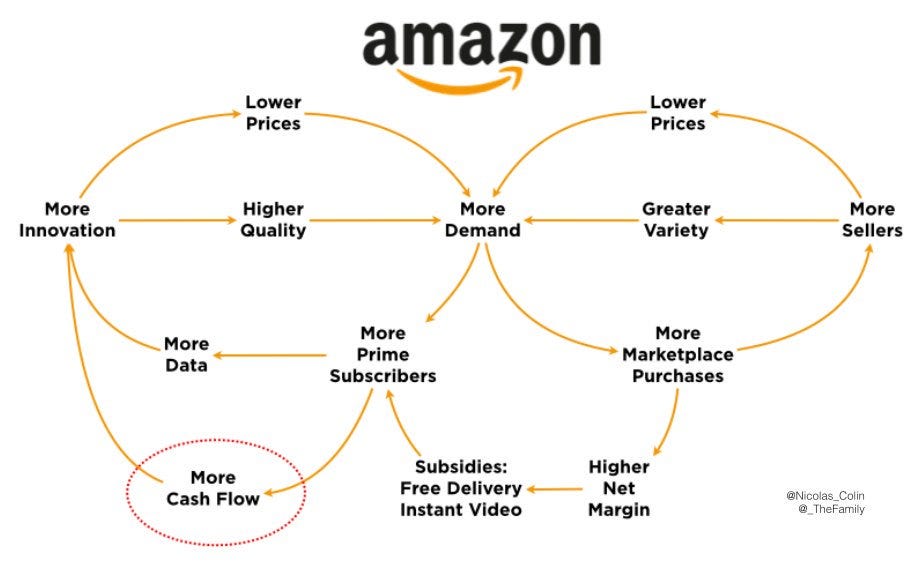

Unlike coupons, & discount loyalty programmes – paid membership creates a higher level of commitment between the business & the customer. The customer commits upfront & the business receives an IOU redeemable by value delivered to the customer. So as Prime membership grew, so did the value proposition of Amazon.com…

It’s a costly endeavour for the business. But creates long term customer value…

But Prime does not sit in a vacuum in the broader Amazon flywheel…

Customer Lifetime Value Through Ecosystems

I’m aware that all examples above are concentrated to one market (i.e US of A) & subjective to retail. But I was keen to understand the applications, particularly when loyalty is baked in the business model. I figured that paid membership programmes’ resonate with households with higher levels of income & discount programmes are tailored to incentivize spend in the broader mass-market customers while loyalty points with cashback sit somewhere in the middle.

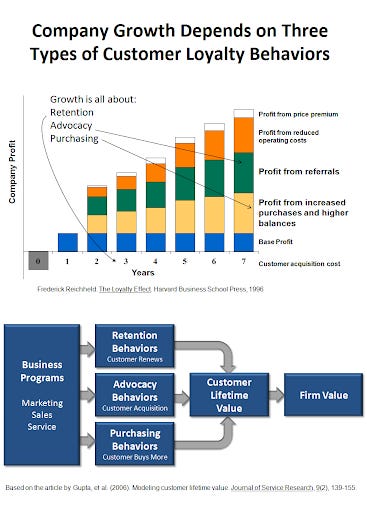

But the main motivation of a loyalty programme for a business is to ensure customer lifetime value. Often it feels gimmicky and incentives don’t align with behaviour but loyalty programmes are important as they advance company growth.

To advance company growth a firm has to ensure 3 key aspects amongst customers are met; retention, advocacy & purchasing behaviours:

Loyalty programmes are used as mechanisms to ensure firm value, so they are indeed paramount to the success of the company. But how do companies choose which programmes are best suited for their customers? As mentioned above, certain programmes resonate with certain customer segments. Though, there is a narrative violation somewhere in that statement.

The answer to this depends, & it truly depends on the customer base & what they value. Often a combination of the aforementioned programmes (Discount Coupons, Cash Back & Membership) works. As customer loyalty programmes become engraved in the DNA of companies, the combination becomes important. Including all 3 means that loyalty programmes become ecosystems with partners.

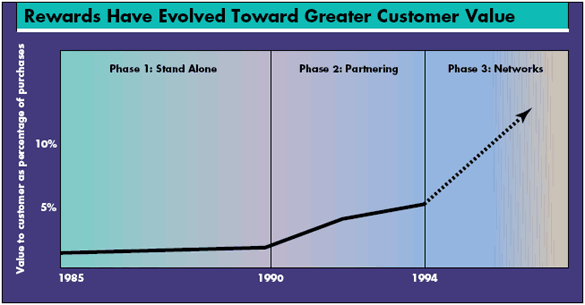

A Harvard Business Review article from 1995 predicted the best loyalty programmes become ecosystems of shared value:

In South Africa, none have personified this more than Discovery’s Vitality rewards programme. 7

As loyalty programmes evolve through the phases, we will see more ecosystem-based programmes8.

“As brands begin to partner around ecosystems, what changes will these partnerships herald for the brands’ pre-established, stand-alone loyalty programs? In the near term, we expect standalone programs will continue to operate beside or within the ecosystem, much as individual airline loyalty programs can function independently while also yielding benefits across an alliance with other airlines. However, as ecosystems grow more conventional and their value becomes more apparent to brands, we envision that stand-alone programs may begin to consolidate under single-flagship ecosystem loyalty programs, or that stand-alone programs may evolve into ecosystems as they incorporate partnerships as part of the core program value proposition.”- Mckinsey

Discovery’s Vitality programme has become more intertwined with its partners. Though still a membership programme the experimentation of Vitality Open shows early signs of how an open ecosystem could potentially drive customer lifetime value. A Vitality lite programme might be an entryway to the broader ecosystem. This could be applied across industries & especially the most innate industry for loyalty programmes, retail.

Maybe the last part of this newsletter should be a newsletter on its own – I don’t know, let me know what you think.

Take care

This story is widely told in this version but there’s no substantive evidence to the claim besides a New York Times article by James J. Nagle on this history of trading stamps.